-

Subscribe to my new Substack!

I’m launching a new Substack exploring rapid prototyping in the age of AI assistants and vibe coding.

-

What I’ve been reading (August/September 2025)

Founders, writers and San Francisco in the 90s with Jessica Livingston and Dave Eggers (plus the 80s with Mitch Kapor)

-

What I’ve been reading (June/July 2025)

It’s Asian Alienation Month with Yoko Tawada (Japan/Germany), Han Kang (South Korea) and Ocean Vuong (Vietnam/USA), with a brief French detour facilitated by Catherine Deneuve

-

What I’ve been reading (in early 2025)

Celebrating Fitzcarraldo Editions and 100 years of The Magic Mountain with Olga Tokarczuk, Colm Tóibín and Thomas Mann (duh)

-

What I’ve been reading in April 2021

Cal Newport on the Hyperactive Hive Mind, with a sidebar on Fred Brooks and the Mythical Man-Month

-

What I’ve been reading in March 2021

Margarette Lincoln on the hip baristas in London of the 17th century

-

What I’ve been Reading in February 2021

Abortive reads with Paul Morely (too much rock criticisims) and with Houellebecq (too much provocation)

-

What I’ve been reading (January 2021)

Reckoning with imperial pasts (with Priya Satia) and with my own so-called immigration background (with me)

-

What I’ve been reading (December 2020)

Wagnerism fallout: Classics by Joseph Conrad and Willa Cather

Salt Mines

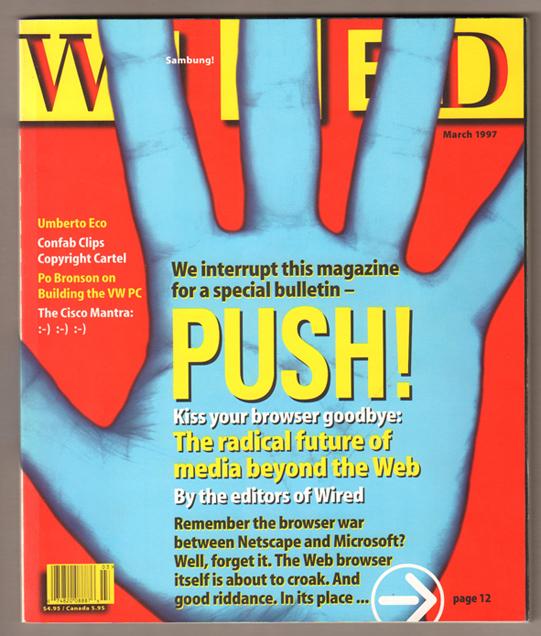

Tales of Electronic Drudgery